Introduction to the Network

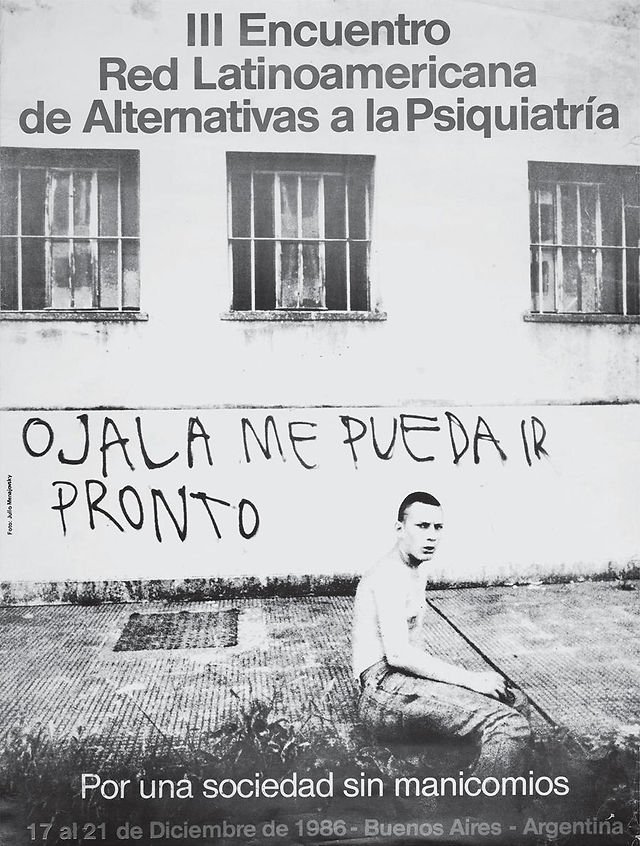

In January 1975, an international group of the psychiatrized, mental health workers, and professionals announced the formation of the Network of Alternatives to Psychiatry (Le Réseau-Alternative à la psychiatrie in French) at a conference in Belgium on “An Alternative to the Sector.” The immediate impetus for its formation was to create some minimal cohesion among the various groups responding to the “sectorization” of psychiatry or “community psychiatry” developments of the 1970s. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, radicals and utopians engaged in mental health work naturally gravitated towards the asylum, the central psychiatric institution, either to try and alter or oppose it. When psychiatry’s center of gravity began to shift with mental hygiene and, even more extensively, when it was dispersed into the “secteur” (in France) or the “community,” such efforts became more disconnected. The purpose of the network was to coordinate international activities and to serve as an organ for mutual support between local groups working to transform psychiatric services in this period of great change. Chapters formed at the sites of the most radical experiments in psychiatry at the time: in New York City around when the Lincoln Hospital was occupied, in Cuernavaca by Sylvia Marcos at CIDOC, in Brazil at the inception of the Movimento Antimanicomial, in France by participants of the La Borde and Saint Alban hospital experiments, in Italy during the movement for Psichiatria Democratica, and elsewhere around the Americas and Europe.

With this present project, we aim to take up the mantle of the Network because we share in their grounding principles, and believe they still need to be asserted today. What unites the diverse contributions of the Network is an implicit understanding that the discipline that responds to the social problem of madness, psychiatry, is not a narrow medical specialty, but is first and foremost a social intervention that would be entirely ineffective were it not for special laws and courts; myriad agents and informants operating in schools, workplaces, and city streets; a complex chain of relations legitimating and actualizing its powers prior to and following the narrowly medical encounter; and structured financial flows organized and disorganized around need, policy, and market incentives. The study of psychiatry is therefore impossible without striving to understand the social totality of which it is a part.

To paraphrase their Statement of Purpose (reprinted here from the appendix to David Cooper’s The Language of Madness), madness is related to the struggles of all workers and the unemployed, since the mad are by and large marginalized workers, out of work, or excluded from work. Madness is not to be “tolerated,” but ought instead be understood as the reflection of contradictions of a common social world. We believe that, no matter how progressive and humane the psychiatrists in question are, madness is and will remain fundamentally irreconcilable in a society oriented around the infinite accumulation of capital, which can only attempt to exploit these outsiders’ labor, or, barring this, exclude, segregate, or eliminate them entirely. For us, the social challenge of madness is not a question of how to integrate outsiders into a machine that produces marginalization and social death, but of concocting strategies capable of undermining and circumventing market imperatives as a necessary condition for recovery. In other words, creating a psychiatry worthy of the name is not possible without the transformation of society. This also means refusing the comforts involved in reducing alienation to a question of discrete psychiatric judgment and refusing to play a repressive role whenever possible.

In positive, practical terms, this approach entails the creation of alternatives and circulation of therapeutic spaces or practices where each party has an active and self-conscious role, analyses of local political developments, strengthening our collective grasp of history to arrive at more coherent expressions of the present, supporting struggles at psychiatric facilities even when they aren’t perfectly theorized or positioned (which is impossible in any case!), researching the function of psychiatric power or the meaning of psychiatric judgements at various sites outside of the traditional hospitals and clinics (prisons, nursing homes, schools, etc), and establishing concrete relations between local groups already engaged in research and organizing. Conferences to share findings, learn from others’ work, or offer critiques were held in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Trieste, New York, and elsewhere through the 70s and 80s. Undergirding all this work is the notion that a network of critical solidarities is more powerful than myriad fragmented acts of desperation rooted in resentments and suspicions.

This work remains unfinished. Since the Network is a flexible, open structure, and because its founding principles are still applicable in the present day, we decided to take up the mantle of this aborted project as a belated North American branch. We happily embrace the contradictions involved in doing so, beginning with the name. First of all, we must remember that the group came about at a time of great change in psychiatry, as it shifted (and not for the first time) from a centralized model organized around the hospital to a decentralized one. The name, in that sense, is a critique of these common sorts of technical fixes in psychiatry. Proposed by Franco Basaglia, the name is, in any sense, strictly incorrect: members were psychiatrists, nurses, and patients/ex-patients. It is a curious sort of “alternative” that operates within the system it is supposed to be an alternative to and constantly speaks to it. Basaglia was certainly not unaware of this when he proposed the name. If a dynamic, socially grounded, and open psychiatry is at all possible, it is necessary to be both in and against the field (that is, to be in and against oneself as someone actively reproducing the field). To be only in it is to accept the inertia and absurdity of the status quo with all its atrocities, genocides, and exploitation as “normal;” to be only against it is to place higher value in a moral posture than in reality, for it amounts to denying the ways even the wildest “alternatives” to psychiatry unconsciously reproduce its most staid and banal presuppositions by other names or simply retreat into the fantasy of a utopia of radical purity (never realized; always betrayed). To us, the name is at once a refusal to accept psychiatry as it is and a refusal to be beautiful souls floating in space whose ideas are too pure and lovely to be tarnished by the actual conditions met in reality.

We take no ownership over the idea by taking on the name. Just as the original Network was striving only to unify and connect efforts already engaged in critical work in the field, our aim is equally humble and small: we only hope to synthesize long-developed ideas, connect trends or concepts, make social connections, and analyze the battleground as active participants. At first, we will primarily use this site to publish lesser-known or untranslated texts on psychiatry from around the world—many from the Network, but many others not—and we will publish the first edition of an irregular print journal soon. We hope that one day the Network can help to connect and coordinate people engaged in resistance movements in the field. As bad as psychiatry looks, we know there are many kind and intelligent people caught in its webs wavering between hope and despair. We believe that it is only by joining our efforts, talking openly and clearly about (and hopefully learning from) our mistakes, and taking stock of what’s concretely possible that hope can transform into action and despair into understanding.

“We want to make réseau [networks].” If you too, want to make réseau, if you want to write or think with us, get in touch.